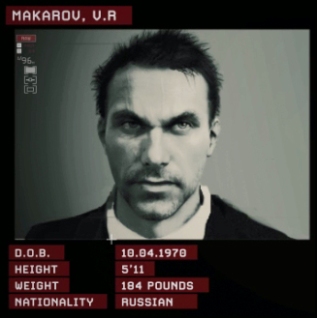

Vladmir Makarov. Ayman Al-Zawahiri. Ask most young men and women hovering around the age of military enlistment which name they know better and see what they tell you. One is a consistent antagonist of the Modern Warfare series. The other is the current leader of Al-Qaeda. Chances are it will be the former.

Of course, these same young people would probably be able to name Link, Master Chief or Kratos before Al-Zawahiri as well. That’s to be expected considering that gaming is the highest-grossing entertainment industry of our era; it’s going to shape our culture. However, unlike Link, Mario or Kratos, Makarov is somehow less fictional. His figure rests in that political uncanny valley that Call of Duty operates so subtly within. He is not an actual terrorist, but he has taken structural and operational cues from the world of terror his writers live within. While Makarov in particular is fake, the political position he occupies is real, even if his real-world counterparts that inhabit it do not adhere to a russian nationalist ideology. There is no Makarov, but, so the series’ writers would like us to believe, such men do exist. The conflict in Call of Duty strives to be one that is actually happening, only with different names, places, countries, and ideologies. These, the game seems to say, are mere details.

And so Call of Duty distills these facts to present the conflict, realer-than-real, as art. And we play it. Millions of us. Oftentimes we bypass the single-player entirely and head straight to Team Deathmatch. Well-balanced and addictive, even those who might take issue with the game’s political leanings (clearly pro-interventionist and sponsored by the US military) indulge in the multiplayer, the “pure” game, because, hey, it’s just fun right? And it is. But that’s the tricky thing about propaganda.

The Greatest Trick The Devil Ever Pulled

Tricky because, like the ideology it furthers, propaganda is at its most effective when it doesn’t announce itself. Great propaganda is not always funded directly by the government and displayed in theaters as such. Rather, it is merely taken for granted. What makes it dangerous is that it does so while still changing our thinking.

It would be difficult to make a case for the single-player story of Modern Warfare not being propaganda. The protagonists are exclusively english-speaking special-forces agents (or defectors in support of the protagonistic powers) intervening to secure worldwide peace against terrorists spreading nationalist-religious ideology or furthering international drug trade. America’s two most-touted philosophical wars, against terror and against drugs, frame the series’ largest antagonists. Furthermore, the protagonists achieve their goals employing surveillance and “interrogation” techniques that violate any number of international treaties and human rights conventions. This, however, is old ground. One can simply “take a side” on these issues and say, “It may very well be a political game, yet, I see what the writers are saying and support their positions.”

However, I feel that the plot itself is a trojan horse. So obviously political, it seems “real”, as though, like it or not, this is war, and if the game makes war seem bad, well, that’s simply because it is. But if Modern Warfare makes war seem “bad” (which even the most vicious war hawks would admit to it being) it’s fault lies in portraying it as bad in the wrong way. Here is where things get interesting because gaming, as a young medium, is an even younger form of propaganda, and it is specifically because it is a game that Modern Warfare is such effective propaganda.

So, not forgetting the plot, lets look at the gameplay. In Modern Warfare, you shoot people who shoot back at you. The people you shoot are bad guys because you are the good guy, meaning that in the context of the game, they are second/third-world terrorists while you are a special ops agent of a first-world government. Right off the bat we have established what the conflict is “about”, and that’s military force. One military force must crush the other to establish supremacy and, if the player is successful, peace. To challenge the player in this show of military force, the opposition takes up ever-greater arms and vehicles, forcing the player to rise to the occasion. The player proceeds through various locales (villages, compounds, ruined city-scapes) in pursuit of the arch-villain while encountering enemy combatants. Stop.

As we said earlier, Modern Warfare is a distillation of the real conflict the US and its allies are embroiled in now. So the conflict described above, though sensationalized, should still strike at the heart of what the war is “about.” But it doesn’t. The greatest challenge to the American military is not the military supremacy of their opponents; Al-Qaeda does not have access to juggernaut armor or a wide supply of WMDs, or even advanced small arms (militants with money can do better than AK-47s). Even if they did suddenly acquire a windfall of money and weapons, in terms of training, manpower, spending and technological progress we completely outrank any militant movement that would target us. Private clandestine patrons or destabilised second-world regimes are totally eclipsed by the national funding of a superpower. The threat is not, and has never been, that the terrorists will “win” and that we will surrender.

Furthermore, even the use of force that the player possesses is presented “at a slant,” to cite Emily Dickinson. It is right, but not quite right in the ways that matter. Consider the use of drone strikes by the player. Always these strikes are used to target enemy forces, often in a sort of escort mission by which the forces on the ground are protected from an onslaught of incoming foes. Always they target armed enemies with the intent to kill, and the only difference between ground warfare and that of the drone is that in the latter the player is both deadlier and more protected. However, with up to 98% of suspected victims of drone strikes being civilians rather than military , can we really accept this view of drones as being anywhere near reality? Here, more than just facts are being changed, the effects of the conflict are twisted themselves. This is no longer mere distillation, this is rewriting history.

Unknown Knowns, Known Unknowns

The same could be said of ground combat, however. When players are breaching military compounds or stealthing their way through villages always their opponents are morally “vulnerable” enough that they can be disposed of without regret (as any act of aggression against them can be reasonably seen as proactive self-defense). But is this the reality of our war? Even when Seal Team Six faced the arch-villain of our war narrative, Osama Bin Laden, in combat, wasn’t the most important consideration not shooting the civilians he was surrounded by?

I’m not trying to argue that Modern Warfare is at fault simply for forgetting to include civilian npcs or meditations on human rights, what I’m arguing is that Modern Warfare ignores these features which form the actual crux of the conflict. In the war we fight now, our martial superiority is unquestionable; the outcome of actual combat is a given in our favor. The trouble, rather, lies specifically in the fact that we don’t always know who we are fighting, and that homegrown resistance movements borne out of popular discontent are comprised of people who blur the line between combatant and civilian. This fact in turn lends itself to the criticism our military has come under for human rights abuses because the conflict “necessitates” civilian casualties, which in turn leads to the military’s increased secrecy and changing of objectives (first WMDs, then stabilising democracy worldwide, now defending our own country against terrorist invasion…) This war has dragged on for more than a decade not because we cannot succeed in armed conflict, but because we are not fighting the purely martial war that we would like, which is exactly the conflict that Modern Warfare attempts to portray.

If my earlier comments regarding multiplayer seemed cryptic, here’s why. The multiplayer portion of the game, in maintaining such apolitical appeal, is actually the most propagandistic part, specifically because it appears apolitical. In the multiplayer portion of the game, the player is free to trick out their gear loadouts to their hearts content with a staggering number of hi-tech options. Afterwards they are dropped into a level which could conceivable frame an armed conflict between a terrorist and military/police faction in which to kill each other. Though they choose their armaments, their loyalties are randomly determined.

The multiplayer acts as sort of a mini-narrative, a conceivable conflict that, even if they surely do not happen as frequently as online matches are played, could occur itself. This is the crucial ideological move, because a conflict between equally armed opponents on either side of this political divide doesn’t happen. The crux of the international war on drugs/terror is that the sides are disproportionate. Could we imagine a terrorist group operating drones with frequency or efficiency as the US government? The same could be said for helicopter attacks, military strikes, rx-cds or even the advanced small arms players employ themselves. Central to the conflict is the fact that one side does possess this technology while the other does not. This material distinction is not a “detail” of the conflict, it is the point.

This is why the multiplayer in Modern Warfare is the most propagandistic facet. Because in removing what the developer’s consider the conflict’s “details” they actual distort its essence. When we accept a conflict between equally powerfully enemies on either side of this struggle as feasible, we have already lost touch with reality.

War…War Never Changes

This line above, a famous quote from the Fallout series, is here as right as it is wrong. The people that want wars fought never want to fight them themselves, and they will always find ways to get other people to fight for them. They will vilify their targets, and they will give those capable of fighting a story to fulfill.

Logistics, however, do change, and they have changed so radically that they now shape the politics of the conflict. We fight a war in which victory or defeat is not a matter of mere casualties or gained ground, but of navigating treachorous terrain political (comprised of laws which aremeant to stop exactly the sort of clandestine operations that the player is executes) and of dealing with the fact that our enemies aren’t purely soldiers.

And culture changes too. While posters and war-reels may have sufficed for superpowers in the 20th century, in the 21st video games, already massively popular among military recruiters’ prime demographic (high school to college age males), form our main cultural input. We should expect them to have a political agenda. We get less and less actual reporting and viewing of the war(s) and more and more stories about it. Our perception of the war(s) is now shaped more by cultural re-telling than actual fact. The danger of video game propaganda is the same fact that makes games such an interesting story-telling medium: the story is more than just what’s said or represented, but fundamentally about how we shape the player’s engagement. In Modern Warfare we engage with the war on terror as an equitable military conflict between two forces distinguished only by ideology. Nothing could be further from the truth.